Birth of a Cluster link

Building Blocks

Using Kubernetes or Google Container Engine there are a few building blocks that you need to understand. There are great docs on their sites, but I’ll give an overview of them here.

Services

Most of the Kubernetes and Container Engine docs start explaining things from the pod level and work up, but I’m going to take the opposite approach to explain them.

A Service is the level of abstraction for something that a client will want to access. That client will typically be either a user (e.g. for a website) or another software component.

When you create a service, you create an abstraction behind which you can do things like load balancing. You are also creating an endpoint that can be accessed elsewhere within your cluster by its DNS name (in much the same way as with Docker links), which makes it very convenient to connect components together.

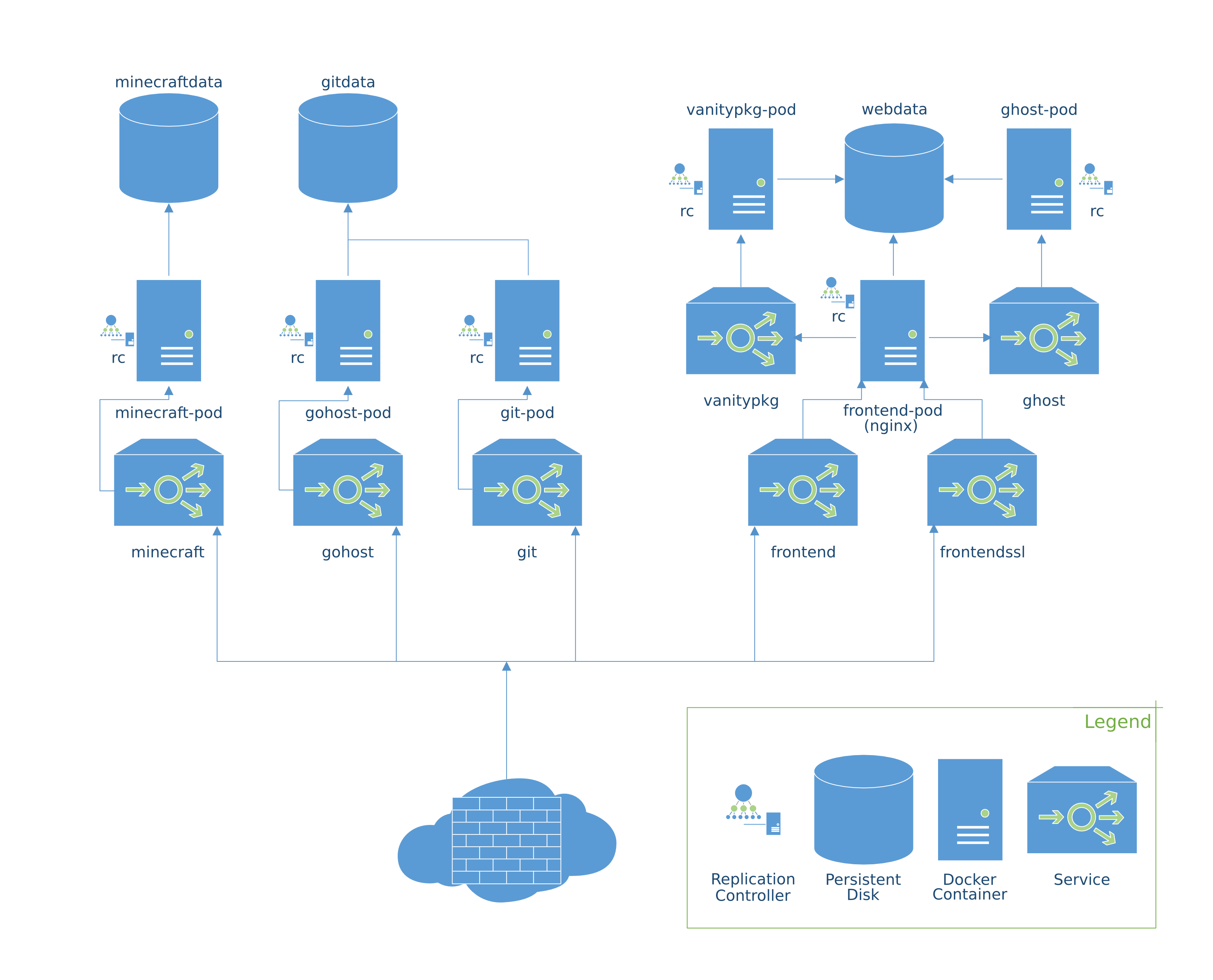

Not all services need be exported outside the cluster. For instance, in my diagram above, the vanitypkg and ghost services are not exposed; they are used by the frontend service (e.g. proxy_pass http://ghost:2468) but have no publicly-routable IP address.

Replication Controllers

Replication controllers are the small bit of smarts around ensuring that the correct number of backends are available for a service. You can use them to scale up and down the number of backends, and they will start up fresh containers if they die (or if you killrestart them 😉).

Pods

In Docker land, the atomic unit is the container. In Kubernetes land, it is the pod. A pod can actually contain multiple containers, if they require shared volumes or are otherwise required to be colocated.

Target Pools and Forwarding

As of this writing, if you’re using Google Container Engine and want to have multiple services running off the same static IP, you will need Forwarding Rules and a Target Pool. A Forwarding Rule forwards TCP traffic to a Target Pool. A Target Pool is an optionally-health-checked set of instances to which traffic can be forwarded. Maintaining these currently requires a bit of manual labor, because it has to be adjusted as instances get added and removed. I am unsure whether this would work if your services do not run on all of your nodes, as (at least theoretically) they could get restarted on a new node and the target pool would not be updated. I hope that this will get easier in the future.

It should be noted that, if you are not interested in static IPs or having multiple services sharing an IP, the Compute Engine cluster implementation of Kubernetes should be able to handle this for you. See the detailed explanations below for more on this.

Nodes

Nodes are the shifting foundations of the cluster. One of them is the master, which runs some central Kubernetes magic, and the rest are simple nodes which act on commands from the master and admins to run containers, update iptables rules, etc. They can be added, removed, etc. as the cluster grows or gets reconfigured.

Observant readers will have noticed that I did not include any nodes in my diagram above. This is for two reasons… one is that it largely doesn’t matter; I could have one or six, and the topology would remain the same; it is also somewhat difficult to draw the lines around what is actually on which node, and I don’t think it would really have helped the diagram.

Building a Service

Now’s when I get to talk about the nitty gritty details of how I got everything set up. I have high hopes that much of this will get better and/or simpler in the future (and I have already seen indications that the v1beta3 API for Kubernetes will be an improvement in a number of ways).

Containerization

The first stage of building out a service is making it run in a container. I’m sure that there are other guides out there about how to collect various things into containers, but if you’d like to take a look at mine, you can find most of them them on my GitHub. They can be as elaborate as my minecraft Dockerfile or as simple as my nginx Dockerfile (which does a bit of file magic and otherwise relies on its parent image).

The biggest trick when containerizing a service is setting up the division between image and volumes in such a way that one can both develop them locally and have them work in production without having to rebuild too frequently or to extract files.

If you’d like some of the wisdom I’ve gleaned from making my Dockerfiles, I’ve attempted to collect some of it in Docker Recipes (also linked from the sidebar menu). I’m particularly happy with the container managment script, which makes it really easy to develop with containers. Suggestions and contributions welcome!

Persistent Disk Setup

Both the Google Container Engine (GKE) and Kubernetes getting-started guides explain how to get a cluster set up, so I won’t go into much detail about that.

I set up persistent disks for each logical segment of my data. Kubernetes supports the notion of a persistentDisk volume, but I had trouble getting this to work consistently, so I used the following procedure:

- Create persistent disk

foodata - Attach to node instance

bar-node-1 - Format with

sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/disk/by-id/google-foodata - Make the mount point (I used

/mnt/foodata) - Add the disk to

/etc/fstaband mount it

I get away with this for now because I am only using one minion node 😈.

Labels

I am using a very simple labeling scheme for the moment. I label every Service, ReplicationController, and Pod with an app label that corresponds with the service, e.g. minecraft or frontend. This makes it easy to tear down an entire stack:

$kubectl delete pod,rc,service -l app=$name

Directory Structure

It is probably important enough to pause briefly here to describe my directory structure. Here’s a general picture:

containers/

kubectl*

setup.sh*

web/

frontend/

controller.yaml

service.yaml

ghost/

...

...

minecraft/

controller.yaml

service.yaml

...

In addition to what I consider to be reasonably self-documenting hierarchy, this allows you to

$kubectl create -f web/frontend/

to grab both the replication controller and service files. If you also have files for development pods, etc. in the same directory, they will also be created.

Replication Controller

My replication controllers are all pretty standard:

(see issue #6336 for details on the commented section)

Among the various directives, you’ll notice the labels and volumes discussed above as well as the gcr.io images discussed in an earlier post. It’s a bit verbose by nature, but I’ve found that the YAML configs mitigate a bit of that compared to the JSON version.

Internal Services

Internal services are easy:

The service is now available to other pods in the cluster using the dns name ghost (or, more specifically, ghost.default.kubernetes.local.). See the cluster DNS addon docs for the gory details. As long as the service exists, its IP address will remain, so you can freely knock over its pods and reconfigure the replication controller without breaking links to it. If you do recreate the service, client applications will break until they re-resolve the IP address (if they do so at all).

External Services

Here’s where things get interesting. I am deviating from the kubectl land pretty significantly here. I suspect that it will get more well-integrated in v1beta3 and beyond, but for now here’s what I have going.

When I started out, I used the built-in createExternalLoadBalancer flag in my service.yaml files for the external services. Some problems with this are described neatly in issue #1161, but the biggest one for me is that I was unable to specify which of my provisioned static IPs was assigned to the loadbalancer that it created. I was hoping that setting externalIPs would give it a cue, but externalIPs seem to be more of an output parameter than an input when using createExternalLoadBalancer (I’ve filed issue #6452 about this).

I used the Cloud Developer Console to set this up, but the same could be done with the gcloud CLI. To replicate my setup using the console, for each service you’ll need:

- A

firewall-ruleallowing traffic to your instances- Networks > Default > New Firewall Rule…

- Source Range:

0.0.0.0/0 - Target Ports:

tcp:1234 - Target Tags:

k8s-clustername-node

- A

target-poolcontaining your instances- Network Load Balancing > Target Pools > New Target Pool…

- Select region and cluster nodes

- A

forwarding-ruleforwarding traffic from your static IP to your instances- Network Load Balancing > Forwarding Rules > New Forwarding Rule…

- Select region and static IP

- Enter port(s) and choose the

target-poolfrom above

You can probably reuse your target pool for all of your services, but I created separate forwarding rules and firewalls for each service.

What I ended up with is this:

Closing Thoughts

At the moment, container engine doesn’t have any support for having a separate instance type for the cluster master node and the minion nodes. Because of this, I’m essentially overpaying for my master node. I would actually like to have different instance types for each node and/or to have some services running on the master, and be able to dynamically add/remove instances. Some of this is handled better by using Kubernetes with the GCE cluster provider, but some of the rest of it is much further down the road.

At some point soon, I will probably try to recreate my GKE cluster using Kubernetes itself, since at the moment it appears that it is lagging pretty significantly in terms of features. It’s a Go project, so there is a nonzero chance that I could find somewhere to contribute or fix a few bugs that I find.